Can a deeply personal act like prayer hold up under the cold scrutiny of science? This question has quietly gained traction in recent years, as researchers across the U.S. and beyond turn their attention to the measurable impacts of spiritual practices. From hospital recovery rates to stress reduction, the intersection of faith and data is no longer just a matter of belief—it’s becoming a field of serious inquiry. Prayer effects scientific studies are shedding light on whether something as intangible as a whispered hope can influence tangible outcomes. For many middle-aged Americans, caught between skepticism and a longing for meaning, these findings offer a new way to think about an age-old practice. They challenge us to reconsider what we assume about the mind, body, and perhaps something more.

The Growing Curiosity Around Prayer and Science

In labs and universities, a quiet revolution is unfolding. Researchers are no longer shying away from topics once deemed too subjective for rigorous study. Prayer, often seen as a private ritual, is now being examined through the lens of neuroscience, psychology, and even clinical trials. The question isn’t just whether prayer “works,” but how it might influence mental health, physical recovery, or social cohesion. A 2019 meta-analysis from the University of Rochester found that patients who engaged in regular spiritual practices, including prayer, often reported lower levels of anxiety during medical treatments. You can explore the study’s framework at University of Rochester Research.

This isn’t about proving or disproving faith. It’s about understanding mechanisms. Some scientists hypothesize that prayer’s calming effect could lower cortisol levels, the body’s stress hormone. Others point to the power of community prayer in fostering a sense of belonging, which itself has documented health benefits. The curiosity is palpable, and it’s drawing in researchers who might have once dismissed the topic as untestable.

Clinical Trials: Prayer Under the Microscope

Picture a hospital room in Durham, North Carolina, where a patient recovering from heart surgery is part of a groundbreaking study. Some patients receive intercessory prayer—prayers offered on their behalf by others—while others do not. The 2006 STEP trial, conducted by researchers affiliated with Duke University, aimed to measure whether such prayers influenced recovery outcomes. While the results were inconclusive on direct physical benefits, the study sparked a wave of debate about how to even design experiments for something so intangible. More details on this landmark trial are available through Duke Health Clinical Trials.

What’s clear is the challenge of isolating variables. Can you measure intention? Does the belief of the person praying—or the one being prayed for—alter the outcome? These trials, though imperfect, signal a willingness to grapple with the unknown. For many Americans in 2025, who often balance science with personal conviction, such studies resonate as a bridge between two worlds.

The Brain on Prayer: Neurological Insights

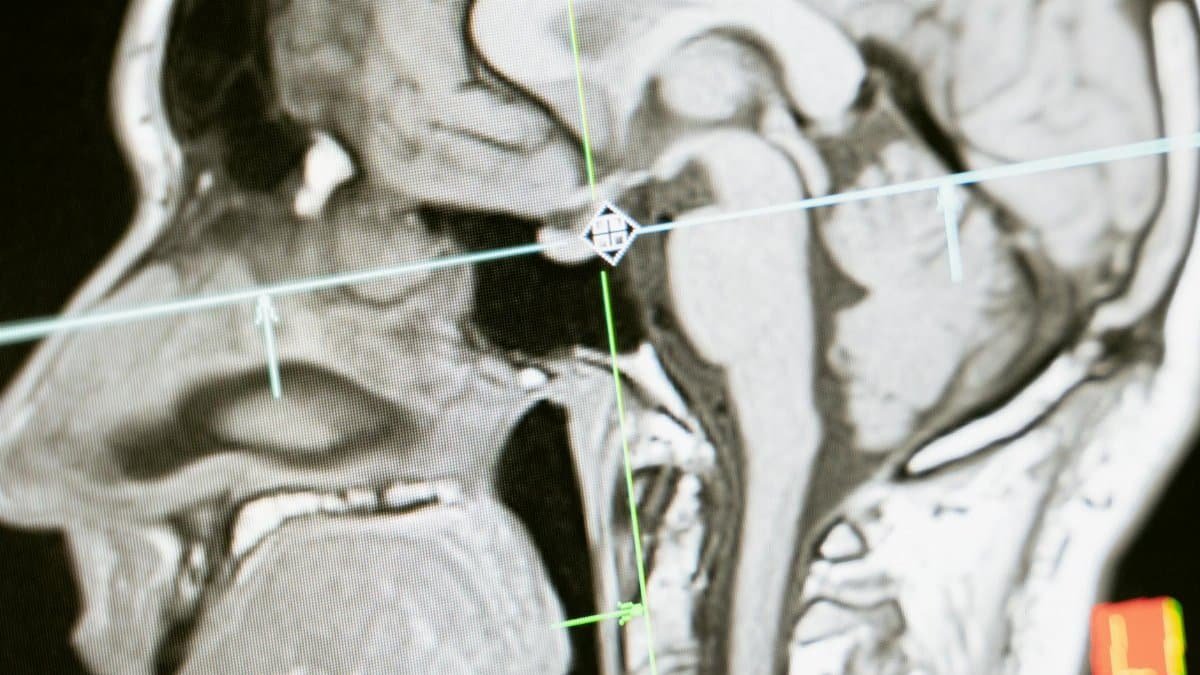

Neuroscience offers another window into prayer effects scientific studies. Using fMRI scans, researchers have observed how prayer and meditation activate specific brain regions, like the prefrontal cortex, associated with focus and emotional regulation. A 2017 study from Columbia University suggested that regular prayer might even strengthen neural pathways tied to resilience against depression. The full implications are still unfolding, but you can read more about related research at Columbia University Research.

One researcher described the brain during prayer as “lighting up like a city at night.” It’s not just poetic imagery—there’s data showing increased activity in areas linked to empathy and self-reflection. For middle-aged readers, who may recall a time when science and spirituality seemed irreconcilable, these findings offer a fresh perspective. They suggest that prayer might be less about external intervention and more about internal transformation.

Stress, Healing, and the Placebo Debate

Not everyone in the scientific community is convinced. Critics argue that prayer’s effects could simply be a placebo—a psychological boost from believing in a positive outcome. Yet even this critique opens up fascinating questions. If prayer reduces stress or improves mood, does the “why” matter as much as the result? A 2020 report from the National Institutes of Health highlighted that stress reduction techniques, including prayer, often correlate with better immune response. Dig into the broader context of such findings at NIH Research and Training.

Consider a woman in her fifties, juggling work and caregiving, who turns to a quick morning prayer for calm. She doesn’t need a lab to tell her it helps her breathe easier. But science is starting to back up her instinct. Studies show that even a few minutes of focused intention can lower blood pressure. Placebo or not, the effect feels real to her—and to millions like her.

Social Bonds: Prayer as a Community Force

Beyond the individual, prayer often happens in groups, whether in churches, mosques, or informal gatherings. Researchers are increasingly interested in how these communal acts might influence well-being. A Pew Research Center survey from 2021 noted that Americans who pray with others report higher levels of life satisfaction, hinting at the power of shared ritual. You can explore Pew’s extensive data on religious practices at Pew Research Center Religion & Public Life.

Think of a small-town prayer circle in Ohio, meeting weekly after a local tragedy. Members don’t just pray—they listen, laugh, and sometimes cry together. Science can’t quantify that warmth, but it’s starting to recognize its impact. Social support, bolstered by shared spiritual practice, often translates to better mental health outcomes. It’s a reminder that prayer’s effects ripple outward, touching more than just the person who prays.

Ethical Dilemmas in Studying the Sacred

Yet, not all reactions to prayer effects scientific studies are positive. Some religious leaders worry that dissecting prayer risks stripping away its mystery. Meanwhile, scientists grapple with ethical concerns: Is it right to turn a deeply personal act into data points? There’s a tension here, one that mirrors broader debates about science encroaching on the sacred.

One anonymous voice, shared in a public online forum, captured this unease: “I don’t want my faith to be a lab experiment. It’s mine, not theirs.” For many, especially in communities where prayer is a cornerstone, these studies can feel invasive. Researchers acknowledge the pushback, often emphasizing that their goal is understanding, not judgment. Still, as studies multiply in 2025, this friction is unlikely to fade.

Practical Takeaways for a Skeptical Age

So, where does this leave us? For those intrigued but unsure, the science around prayer doesn’t demand belief—it invites curiosity. Start small. A few minutes of quiet reflection, whether labeled as prayer or not, might shift your day. Studies suggest it’s less about the words and more about the pause, the intention to step outside the grind.

There’s no need to choose between faith and reason. The emerging field of prayer effects scientific studies shows they can coexist, each informing the other. For middle-aged Americans, often navigating loss or transition, this research offers permission to explore. It’s not about answers. It’s about asking better questions—about health, connection, and what it means to hope in a world that often feels uncertain.

A certified hypnotherapist, Reiki practitioner, sound healer, and MBCT trainer, Christopher guides our journey into the spiritual dimension, helping you tap into a deeper sense of peace and awareness.

Disclaimer

The content on this post is for informational purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional health or financial advice. Always seek the guidance of a qualified professional with any questions you may have regarding your health or finances. All information is provided by FulfilledHumans.com (a brand of EgoEase LLC) and is not guaranteed to be complete, accurate, or reliable.